We are all used to bad weather in the UK – it never rains but it pours, and autumn and winter storms are nothing new. So why have the Met Office issued their highest level of weather warning over such a large area?

Blog post by Dr Kate Smith of the Flood Innovation Centre and Dr Rob Thomas of the Energy and Environment Institute, University of Hull

Weather warnings are related to the expected impacts, so although the forecast winds and waves are largest in South Wales and the South West of England and forecast winds slightly slower in the South East of England, the red warning has been extended to the South East because of the huge population density and value of property.

Whilst Atlantic storms are something we experience regularly in the UK, and most often affect the South West, flood risk management authorities get most concerned about storms when they coincide with other environmental peaks such as particularly high tides. Again, these high tides are something that happen regularly (and predictably) and are in themselves not usually of big concern. But when they coincide with a significant storm, the combined effect of a storm surge and the higher tide can be devastating.

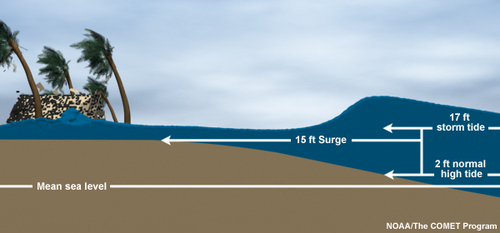

A storm surge is a result of two factors. First, the lower pressure in the centre of the storm “sucks” the water upwards, raising water levels. Second, the wind pushes water from the back of the storm to the front of the storm, creating a long wave with a crest in front of the storm. Spring tides occur when there is a new moon or a full moon- then the sun and moon are aligned and their gravitational pull acts together to raise the ocean up a bit. Combine a storm surge and a spring tide and you get a lot more water moving towards the coast and the potential for major flooding.

In the case of this morning, the storm surge caused by Storm Eunice coincides with a Spring tide. For the Severn estuary, which already experiences some of the largest tides on Earth, the addition of the storm surge on top of that tide had the potential to be extremely serious, with widespread and sudden flooding along the coast and up through the lower river catchment. The system used by the Met Office and Environment Agency to generate weather and flood warnings suggested that there was a high probability that the storm would hit the estuary as the Spring tide came in, and so severe flood warnings were issued along the Severn Estuary and flood protection protocols were put in place.

So far, it looks as though the Severn has escaped the worst combination of weather and tide: high tide was between 7 and 9am this morning; low tide will be between 2 and 6pm this afternoon. Model predictions are that the peak storm surge will occur nearer the low tide than the high tide. Had it been the other way around and we would be looking at huge coastal flooding happening at the same time.

A similar thing happened in the Humber estuary on 5th December 2013. The peak water level at Immingham on the south bank of the Humber was 5.31m; the storm surge component of this was 1.58m but the peak surge was 1.97m. Had the peak surge coincided with high tide, we’d have been looking at 40cm higher water and Hull city centre would have been under 25cm of water. As it was, 264 homes and businesses were flooded in 2013, which led to many of them deciding to increase their property and business flood resilience.

The Flood Innovation Centre works with businesses and community organisations to help them become more flood resilient and to develop new products and services in the flood resilience sector. If you’d like to know how we can support you please contact flic@hull.ac.uk